Since I last wrote on stippling or half-toning algorithms in Non Photo-Realistic Mona Lisa, I have developed a new image tiling algorithm and finalized my plans and procedures for sharing python code.

Algorithm Update

My original algorithm divided the input photo into n equal black rectangles by slicing in one direction, then each of these rectangles was divided, … Although this method produced very recognizable results, it also produced patterns which were artifacts of the algorithm in the image.

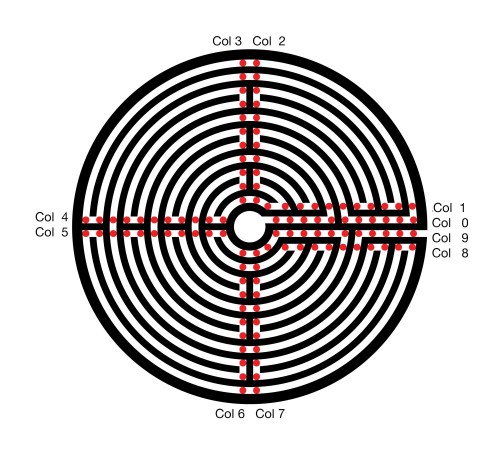

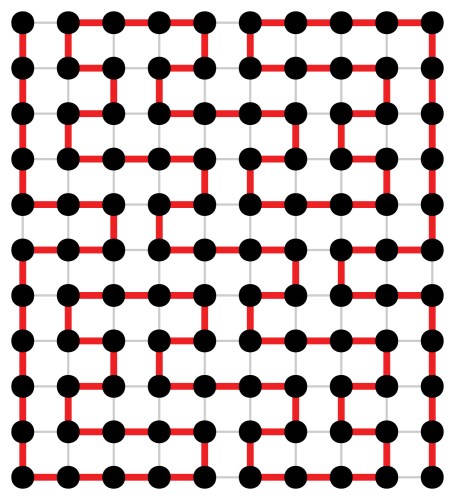

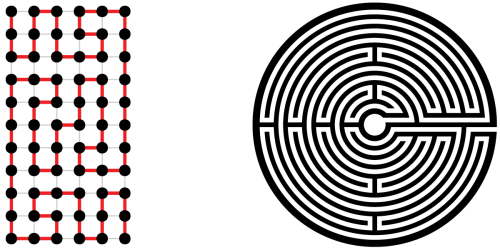

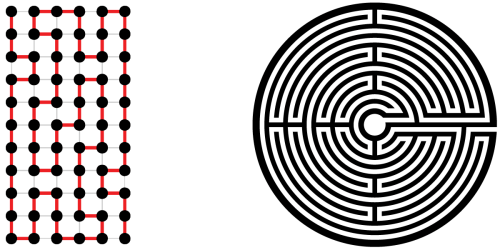

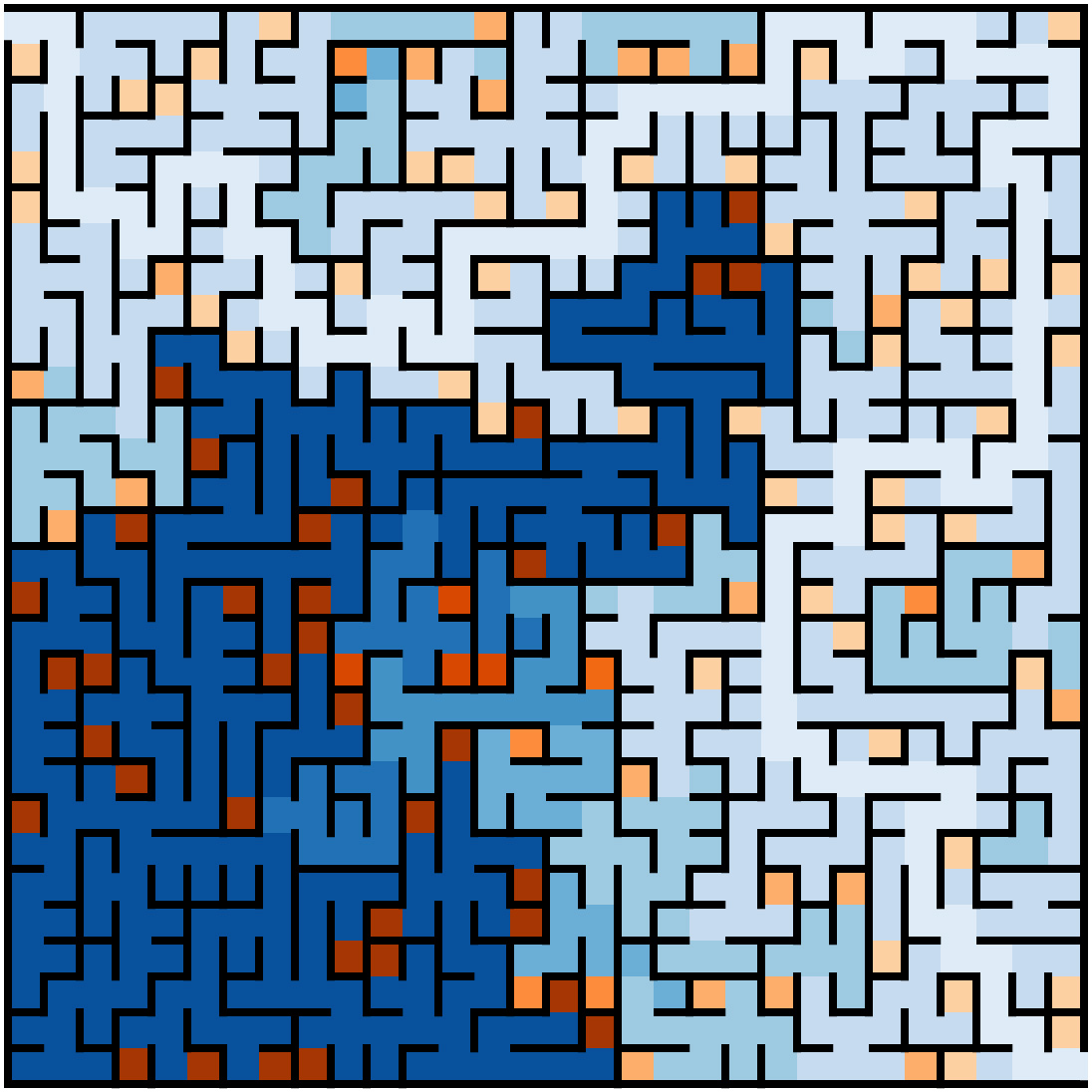

The two images below illustrate the first slice into 5 rectangles of equal blackness, followed by a second slicing of each of the 5 into 5 more using the original algorithm.

In an attempt to break up the artifact patterns, I have developed a new approach which uses recursion to slice up rectangles. Instead of selecting n slices of equal black ink the new code first looks for the most significant slice it can remove containing 1/N’th of the ink from either end and then recursively calls itself to process N-1 slices which may now switch directions.

The figures above illustrate the approach for division by 5 followed by a second division by 5. First, the algorithm finds the most massive horizontal fifth at the top end of the verticle image. Next, one-fourth of the left side of the remainder is chosen. Then the top third of the rest is selected, and then the final portion is split into left and right. In the second pass, illustrated by the image on the right, each of these rectangles is processed similarly. Note that the rectangles appear more random than those generated by the original algorithm.

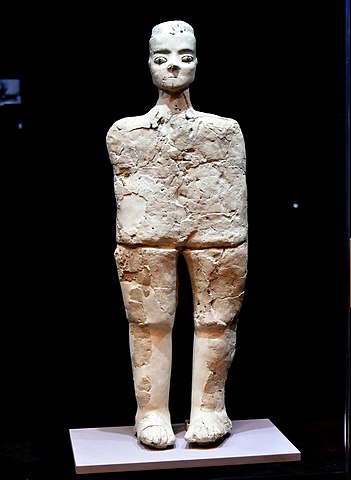

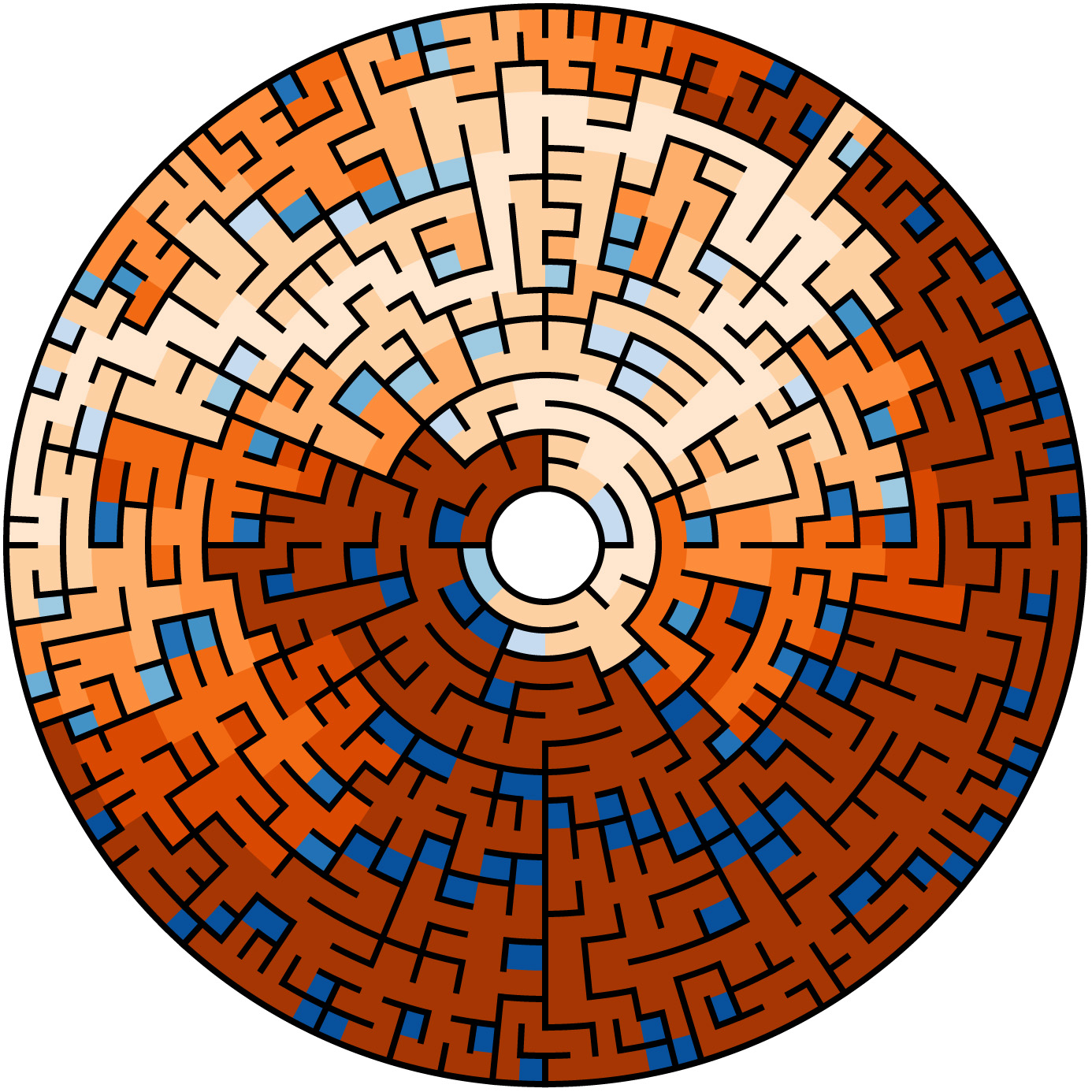

What are these algorithms for. First for some images the output rectangles have an incredible abstract beauty of their own. My future plans include both geometric pattern half-tone images, were an icon of the correct size represents the actual black content, and photo mosaics where a small photo is placed in the center of each rectangle and when viewed from a distance they merge into the original image.

Run The Code

The big news is, I have finalized the procedures I will use to share the code I write. Google’s Colabortory provides a Linux processor on which you can execute Python Jupyter Notebooks. The easiest way would have been to store my Notebooks on a Google Drive and share them granting permission to view and comment to all. However, the process of transferring ownership of a copy so that it can be executed and/or changed without modifying the original seemed overly complicated. In the end, I decided to use Github.com for my storage of Notebooks. Colabortory provides tools which open my Github repository Notebooks as copies owned by you, Oh, you will need a Google account. If you’re not currently logged in, colaboratory provides a button to start the log in process.

Colabortory provides menus and buttons in the toolbar at the top of the page. Of specific interest now are the file menu which will allow you to save the Notebook (file type .ipnb) on your Google drive, in Github, or download to your computer, and the run menu in which the run all command can be used to execute the notebook.

At this point I suggest you open the Photo_SlicerTiler notebook. Click on the Icon below to open the Notebook in a new Tab or Window (depending on your browser settings).

Under the Notebook toolbar, you will find two window panes. To the left is a Table of contents which allows navigation through the notebook and to the right the notebook code. The right pane is divided into cells which contain either text (Markdown formatted) or code. The runtime menu controls the execution of the notebook. Code cells can all be executed one after the other with “Run all,” or a few cells can be run with “Run Selected” or they can be “single stepped” with “Run the focused cell.”

The code cell of the first section “Setup Python environment” first checks for the existence of the Cairo drawing package and the Mona_Lisa.jpg file. If both exist, it exits. This avoids the setup overhead for multiple executions with changing parameters. The Setup also produces a Log to aid in locating problems.

Three Linux commands are used in the setup. Note the “!” is used to execute the Linux command from the python environment. When the “!” is used the output of the Linux command is returned as a string to python.

“apt-get” is part of the Debian/Ubuntu Linux package management system and is used to install libcairo2-dev the Cairo library.

“pip3” is the python3 package manager and is used to install pycairo the python interface to the binary library.

And finally “wget” is used to download Mona_Lisa.jpg from the drive.google.com using https. The sharable link to Mona_Lisa.jpg on my Google drive is https://drive.google.com/open?id=1_hUkSmQjXfxMwq170pOlRxdgf7hajgHd

The portion of this link following “id=” is the Google fileID. These fileIDs can be used in wget commands to download to your Colaboratory environment. The required form is:

wget -O ColabFileName “https://drive.google.com/uc?export=download&id=FileID“

The capability to run sharable notebooks from Github and the capacity to access data from a google drive with wget are two pillars of secure runnable shared code on Colaboratory.

Sections 2 and 3 are “libraries”. Section two defines the sliceIm and tileIm functions which implement the algorithms described at the top of this post. drawImage a function defined in section three creates a scalable vector graphics drawing of the rectangles produced by sliceIm or tileIm.

A great advantage of Cairo when used within Colaboratory/Jupyter notebooks is that regardless of the graphics backend used (SVG, PDF, JPEG, Microsoft-Windows …), one can always produce a PNG image file by calling cairo.Surface method write_to_png. The displayImage function uses write_to_png to produce an in-memory ByteString. The IPhython.core.display Image method converts the ByteString to type png image so that the IPhython.core.display.display method can produce the drawing in the notebook output.

The first cell of section 4 (The main program) first imports the required python packages and then reads the input image. Open, from the Python Image Library (PIL), supports most computer image file formats. Convert is used to convert color photos to black and white using industry standard conversion. The last two lines of the cell use the numpy package to produce a “negative” image array with black as 1.0 and white as 0.0.

The next cell contains a new construct. It implements a notebook form. A form is a simple user interface for entering data into the program. When you change data in the form, the code changes to assign the new value.

The second portion of the cell defines a main procedure which iterates over the divisors entered and slices or tiles each rectangle by the current divisor. Why is main defined and not just scripted python? Because if it’s a script the Cairo surface will remain defined, the output file will not be closed, and the download cell below will download an empty file. When we exit main, the surface is freed, and the file is closed.

The last two cells are conditional, on the checkbox of the form, downloads of the output and setup.log.

Please post comments about this blog using the comment link. If you have issues, suggestions, improvements etc. regarding the code go to https://github.com/doug14226/colab1/issues and open a new issue.

Next code example will geenerate mazes, until then try a little programing, add code to upload your photo and change the code to use it.