Labyrinth carved on a pillar of the portico of Lucca Cathedral, Tuscany, Italy. The Latin inscription says “HIC QUEM CRETICUS EDIT. DAEDALUS EST LABERINTHUS . DE QUO NULLUS VADERE . QUIVIT QUI FUIT INTUS . NI THESEUS GRATIS ADRIANE . STAMINE JUTUS”, i.e. “This is the labyrinth built by Dedalus of Crete; all who entered therein were lost, save Theseus, thanks to Ariadne’s thread.”

Photos and quote by: Myrabella / Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA 3.0

For years I thought of labyrinths as simple objects. If one followed the path, the designer presented no choices. Eventually, one would exit or die in the mouth of a monster. The outcome was not your choice but the intention of the designer of the labyrinth.

Then in the fall of 2018, my attitude changed. While visiting Lucca, I had a wild thought. I would create mythical labyrinths of Lucca. They would be of the same species but different individuals.

What is the genome of the Lucca labyrinth? I had no idea. How would I design mythical descendants? Again, I had no idea. However, I did know how to start the design of a computer program. First, I needed a vocabulary to describe the program. Graph theory, a branch of mathematics that describes things (called vertices or nodes) and their relationships (called edges or links), provided that vocabulary. The following figure is a simple graph.

If node one is a labyrinth entrance and node six the exit. Then "walking" 1-5-4-6 is one of many paths. However, for my mythical labyrinths, I need a Hamilton path. Hamilton paths are the result of self-avoiding walks that visit all nodes. For this graph, 1-5-2-3-4-6 is a Hamilton path.

My design uses a graph that maps each location (the nodes) to neighboring nodes (using edges). The program then iterates randomly over Hamilton paths through the nodes. It halts when it finds a mythical Lucca labyrinth.

I plan two more posts about this work.

-

The next will describe the method of iterating over possible paths.

-

The final post will describe the halting condition. That is the definition of mythical Lucca labyrinths.

The remainder of this post addresses the graph design and its relationship with the drawing of the labyrinth.

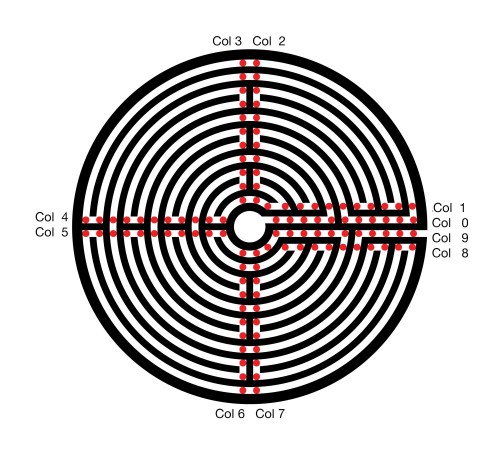

Returning from Lucca, I printed an drawing of the labyrinth. Taking a red magic marker, I attempted to discover the form of a graph and its path, which could describe both the Lucca labyrinth and its mythical siblings. The first and unmistakable set of nodes follows.

The resultant graph and path, in red, follow.

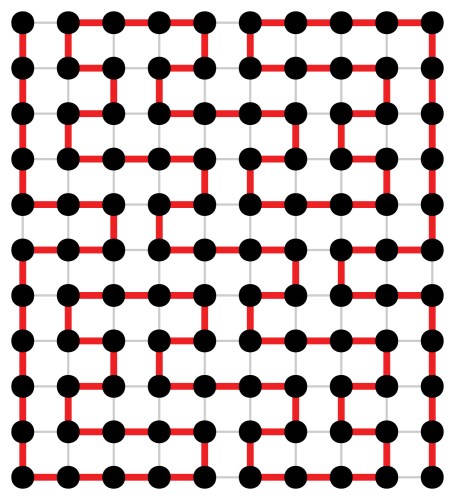

The top row of the graph, row 0, describes the central ring of the labyrinth. The bottom row, 10, maps the outer ring of the labyrinth. The exit from the labyrinth’s central court, column 0, is to the left and the path to the exterior is to the right. The red Hamilton path describes the route of the labyrinth.

This eleven by ten rectangular graph might satisfy my needs. However, it has a fatal flaw. In every row, the path connects the odd columns 1, 3, … 11 to the even column to their right. My mythical labyrinths will also require these connections. Without all of these connections, some of the sweeping arcs will be missing. These arcs are a chief feature of the Lucca labyrinth and, therefore, also required for my myths. Using this Graph, the search space for my mythical labyrinths is very substantial. The program run time will be significantly increased, probably beyond my lifespan and that of my computer.

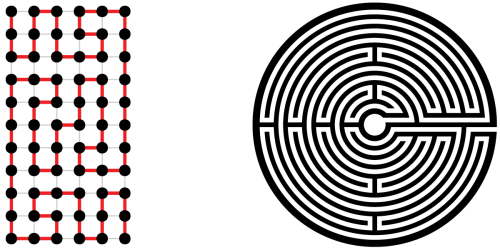

Replacing each pair of nodes, which will always be connected, with a single node avoids checking 44 edges to ensure their presence. However, the new graph does not contain information on every turn. The labyrinth drawing software must cover this missing information. The following analogy illustrates my design. Think of the labyrinth interior columns as a snowboarder performing on four connected half-pipes. When our snowboarder enters the half-pipe, gravity and then inertia takes him with no alternatives to the opposite edge. Then if directed to the next column, the snowboarder exits the half-pipe. When remaining in the half-pipe, the snowboarder first turns 180 to the next row. Then once again, gravity and inertia drive our snowboarder back across the half-pipe.

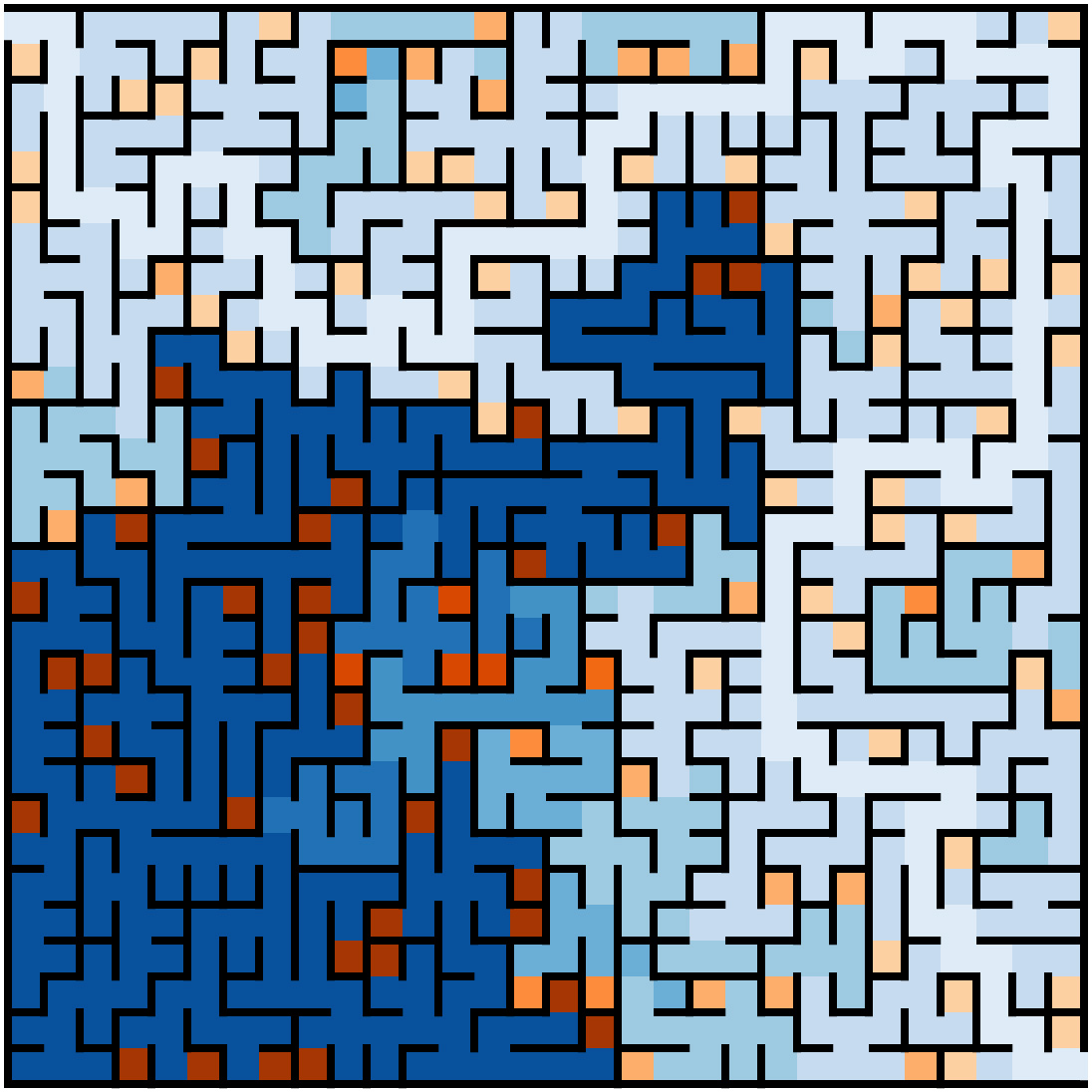

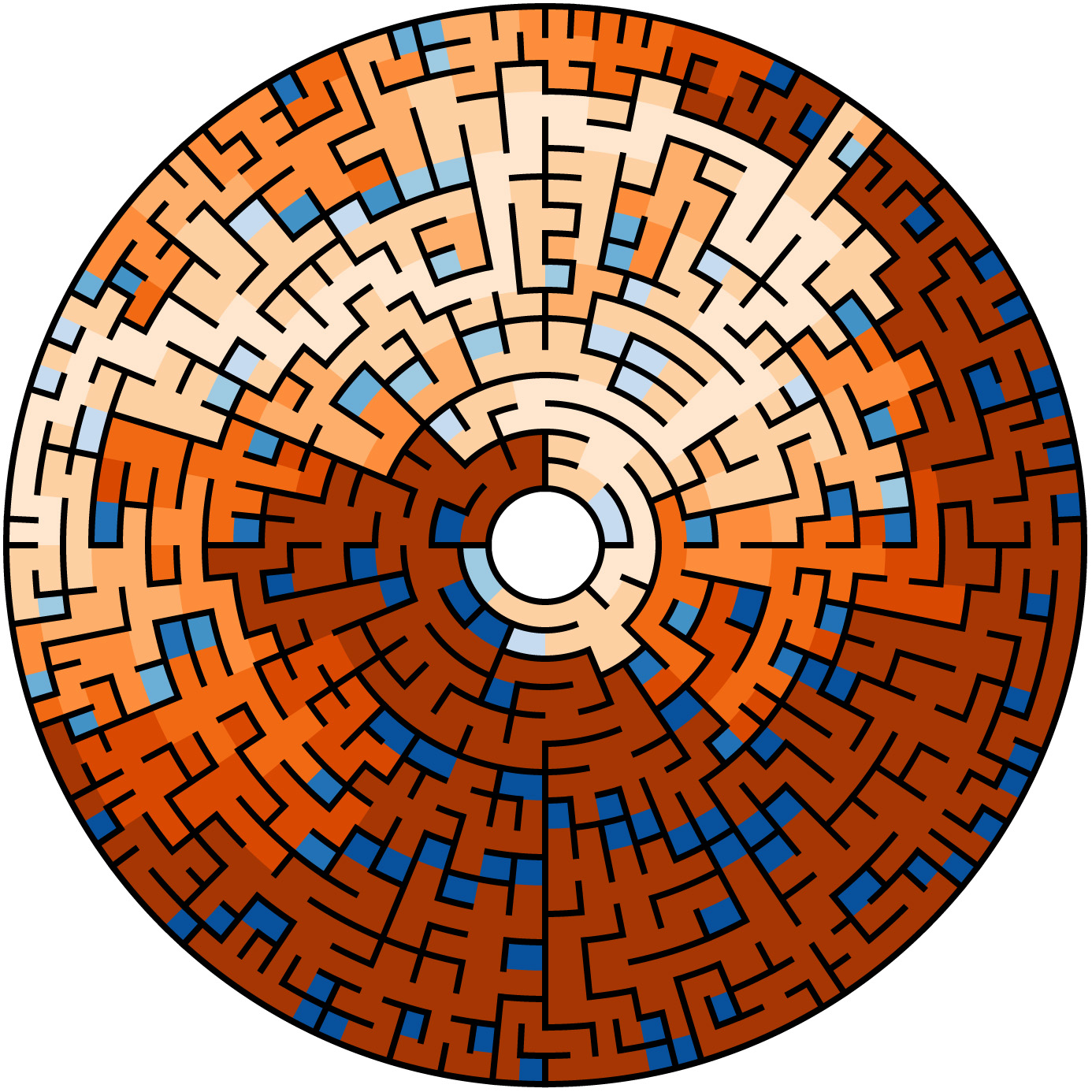

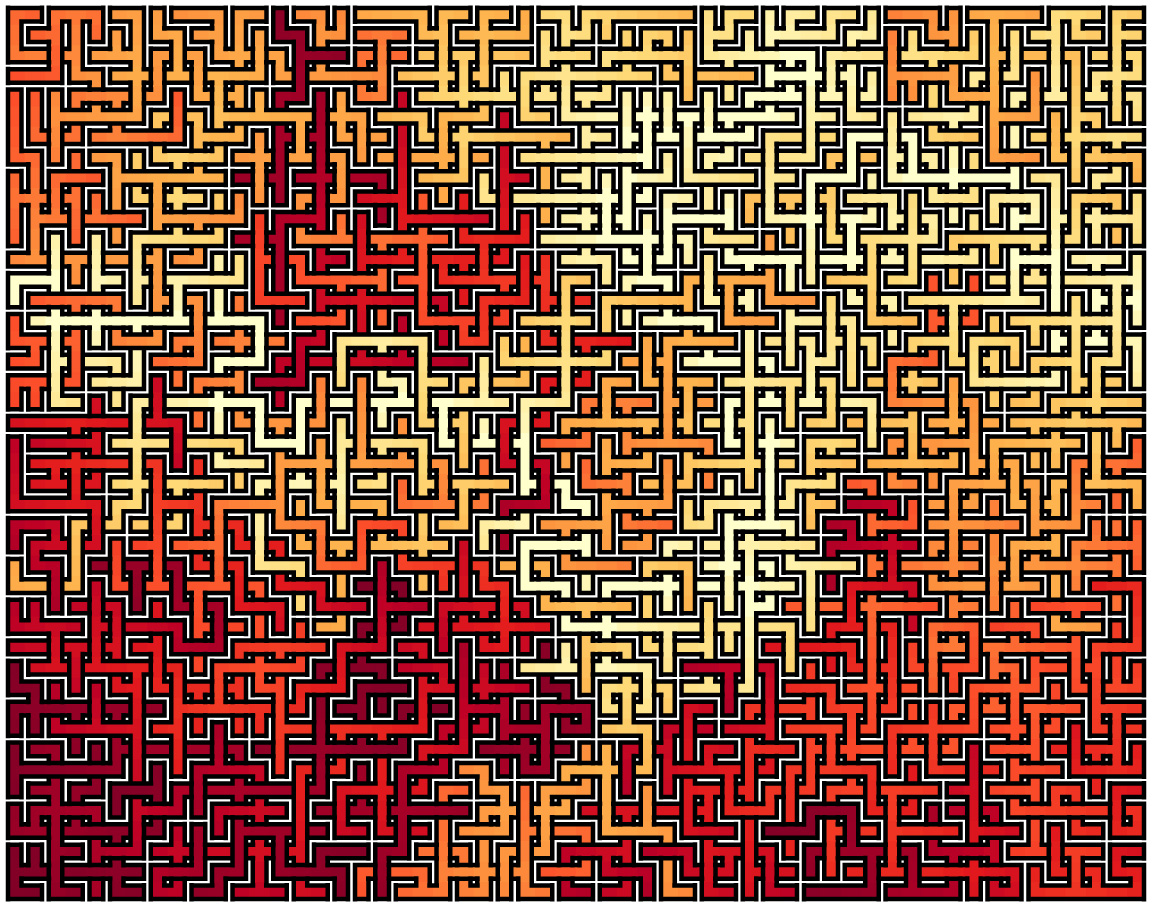

The eleven by six graph and drawing for the Lucca labyrinth follow.

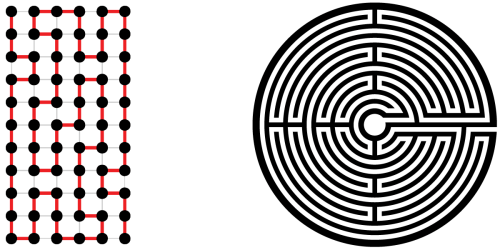

In closing, here are two of my mythical Lucca labyrinths.