Did you ever read a book about a place, then later plan a trip there and fail to integrate those two activities in your mind? Last year when we prepared for a trip to Matera in the Italian region of Basilicata, I never connected my memories of “Christ Stopped at Eboli” by Carl Levi with the journey. Levi’s book introduced me to the rugged, parched terrain of south-central Italy and the “feudal” organization of society there before World War II. But that knowledge seemed to have had nothing to do with our travel south.

For the American ear, a more straightforward translation of “Cristo si è fermato a Eboli” would be “Modern Western Civilization never proceeded South of Eboli.” In the book, Carlo Levi’s banishment from his home in Piedmont to the village of Gagliano, Lucania happened because of opposition to the Fascists and the Abyssinian War. Gagliano is a name only for the book. The actual location of Levi’s banishment is Aliano fifty miles southwest of Matera.

Why do we today call this region Basilicata and Levi called it Lucania? Lucania is a very ancient name for the area. The Lucani (Lucanians) ruled this region until conquered by the Romans during the second Punic war. The name that was good enough for the Romans was good enough for the Fascists in their recreation of the empire. The name Basilicata, the current name, comes from the period of Byzantine rule after the fall of the Western Roman Empire.

Three things stick in my mind as features of this world. First is rugged terrain and the extreme vegetation which grows on this hard earth.

The second memory is of Levi’s sister’s horror at the poverty she witnessed in Matera while visiting her brother. Following winding mule paths into the Sassi, she saw peasants living in caves. The caves housed both the families and their animals, people, pigs, mules, and chickens living in shared rooms. The ceiling of each of these caves, with its stone facade, formed the street and floor of the cave above.

My final memory from Levi’s book is the complete social separation between the professional and landowning class from the peasants. The top society lived, with some leisure, comfortable lives. Every day peasants suffered on the hard land.

This hard life of the peasants started to change in the 1950s as the Italian government closed the slums of the Matera Sassi and moved the poor to modern apartments. Also, a new functioning social safety net guaranteed health care and eliminated starvation.

On our third and final day, we left the city of Matera and explored the much older ruins of houses and churches east of the ravines of the Sassi. This area, the Parco della Murgia Materana, witnesses 7,000 years of human society beginning with the Neolithic period and reaching its peak 1000 years ago. After these early developments, civilization had moved to the location of modern Matera.

The park visitor center, Jazzo Gattini, is a 200-year-old “sheepfold” were shepherds sheltered their flock for the night. The center provides tours, an educational facility for students of all ages, video facilities, maps, and food for guests. Our experience here was way beyond expectations. One of the English speaking members of the staff sat down with us and provided the history of the area and recommendations given my/our hiking capabilities (he gave us more credit for abilities than we deserve).

After watching several videos, we headed off to find the 7000-year-old Neolithic village of Murgia Timone. In the first few steps, I made a navigational error as I walked east down a dirt road rather than along a footpath. After covering a greater distance than indicated on the map and now headed southeast not east, lost, we turned left into a long driveway toward some older buildings. Although the buildings were unused, there were several campers with recreational vehicles in the area. Approaching the first vehicle, we were happy to determine the occupant spoke fluent English. Unfortunately, he was of no help as he had just arrived but did recommend we try the older Italian man at the far end of the area. Michele, who only spoke Italian, was checking his beehives in the area. He had known about the Neolithic village for fifty years but had never taken the time to see it. He would be happy to take us if we waited for a few minutes, as he too wanted to visit. I was surprised to find we were only five minutes away from the nearest dwelling.

There were six homes, all very similar. And stone curbed “streets” lead between the houses. While walking past the caves, Michele pointed out the herbs growing wild at our feet. He picked up sage, oregano, and thyme. Crushed each in his hand and let us smell the great aromas. Then he dropped then on the ground as it was illegal to carry them from the park. My favorite herb was the wild saffron crocus.

Usually, these flowers would bloom in the warm spring when his bees were very active. However in recent years, it was far to dry in the spring, and now the crocus bloomed in late October and November when it was too cold for his bees to fly. Basilicata crocus honey will soon be another loss to climate change.

Leaving the Neolithic village, Michele offered to show us the Belvedere panoramic lookout across the ravine from the Sassi. There continuing our conversation, Michele described his childhood in the Sassi. Ten years after his birth, Michele’s family had been one of the those moved from the cave homes in the 1950s.

On leaving the Belvedere, we asked Michele to pose for a photo with us. Sadly he refused. Our acquaintance was one of those exceptional unplanned surprises that seem to happen when traveling.

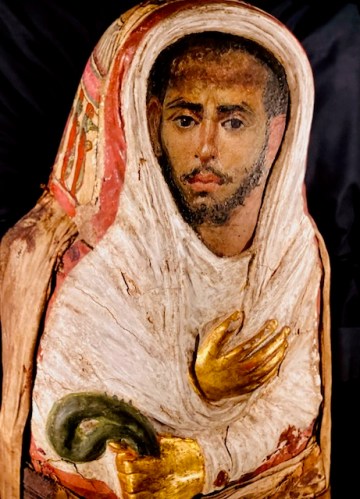

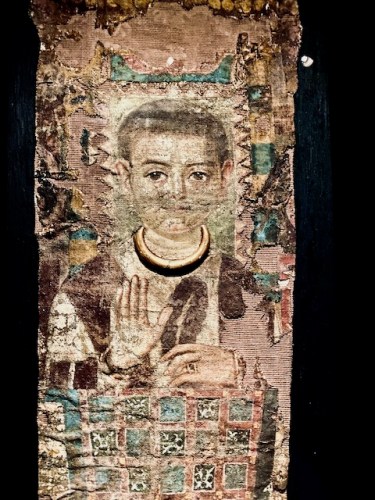

One thing which Levi’s book could not prepare me for was the stone churches (Le Chiese Rupestri) of Matera. Some of these churches are older than a thousand years. These are creations of negative architecture. The columns and arches which mimic those in churches made of quarried stone are what’s left after the rock was excavated. The earliest were dug (I almost wrote built), on the east side of the ravine by Byzantine monks in the eighth century. These monks were fleeing religious persecution for there creation of images. Most of these images have been ravaged by time, water, and unfortunately collectors of artifacts. However, what remains has a new beauty as the remnants of the art merge into the rock.

This year, 2019, Matera has been selected as the European Capital of Culture. Click here to learn more. For decades the Sassi had remained uninhabited. But today the former slums are populated with hotels, B&Bs, museums, and shops of all kinds as well as private homes. Luckily this restoration has preserved the beauty of this ancient city.